Double Trouble: Bicuspid Aortic Valve (BAV)

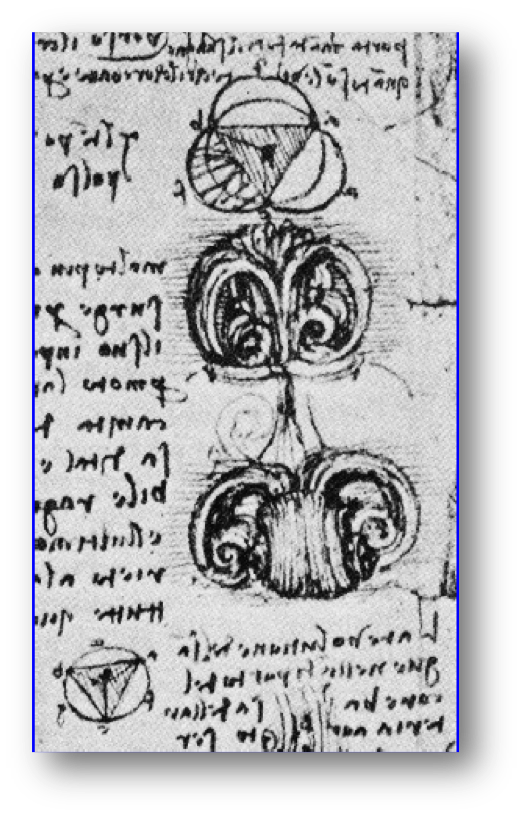

Let’s discuss what is a bicuspid aortic valve. The main valve of the heart - the aortic valve - is an incredibly beautiful structure with a level of design complexity that even the brilliant Renaissance artist and scientist, Leonardo da Vinci, marveled at.

All medical students and physicians have studied heart anatomy and know about the aortic valve.

However, for specialists like myself, there is a level of fasciation and depth of understanding that is light years beyond introductory level anatomy.

Today’s discussion focuses on bicuspid aortic valve disease. At the end of this dissertation, you will understand why I entitled it “Double Trouble”.

Some people are born with an abnormal aortic valve - called a “bicuspid aortic valve”, also abbreviated BAV.

Let’s get started.

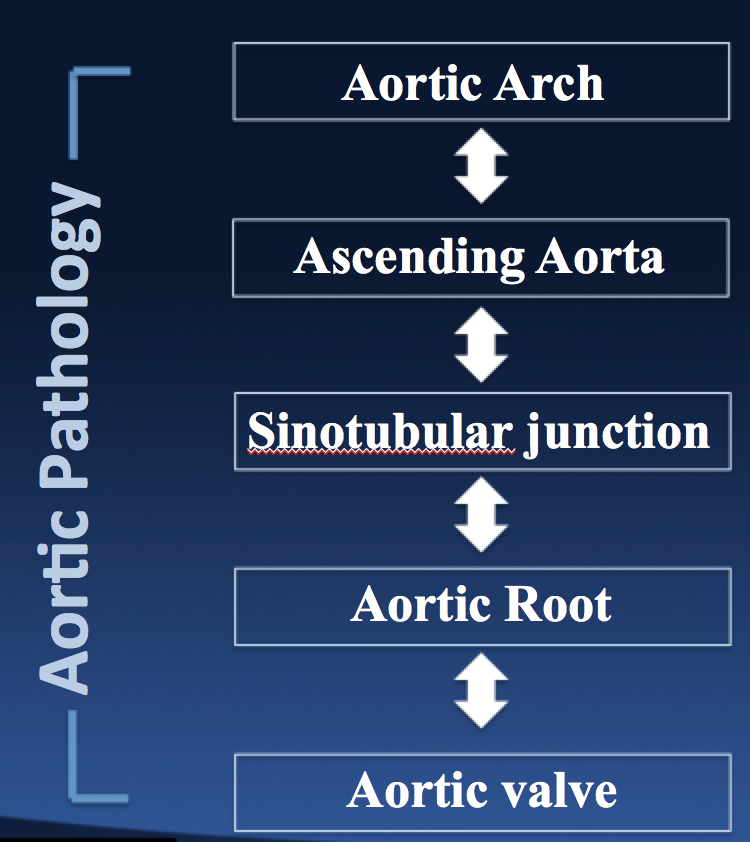

The “normal” aortic valve is located at the transition between the left ventricle of the heart and the aortic root. The left ventricle is the muscular chamber of the left side of the heart which pumps (“ejects”) oxygenated blood to the body. Blood leaving the heart crosses the aortic valve and enters the aorta (the major blood vessel of the body).

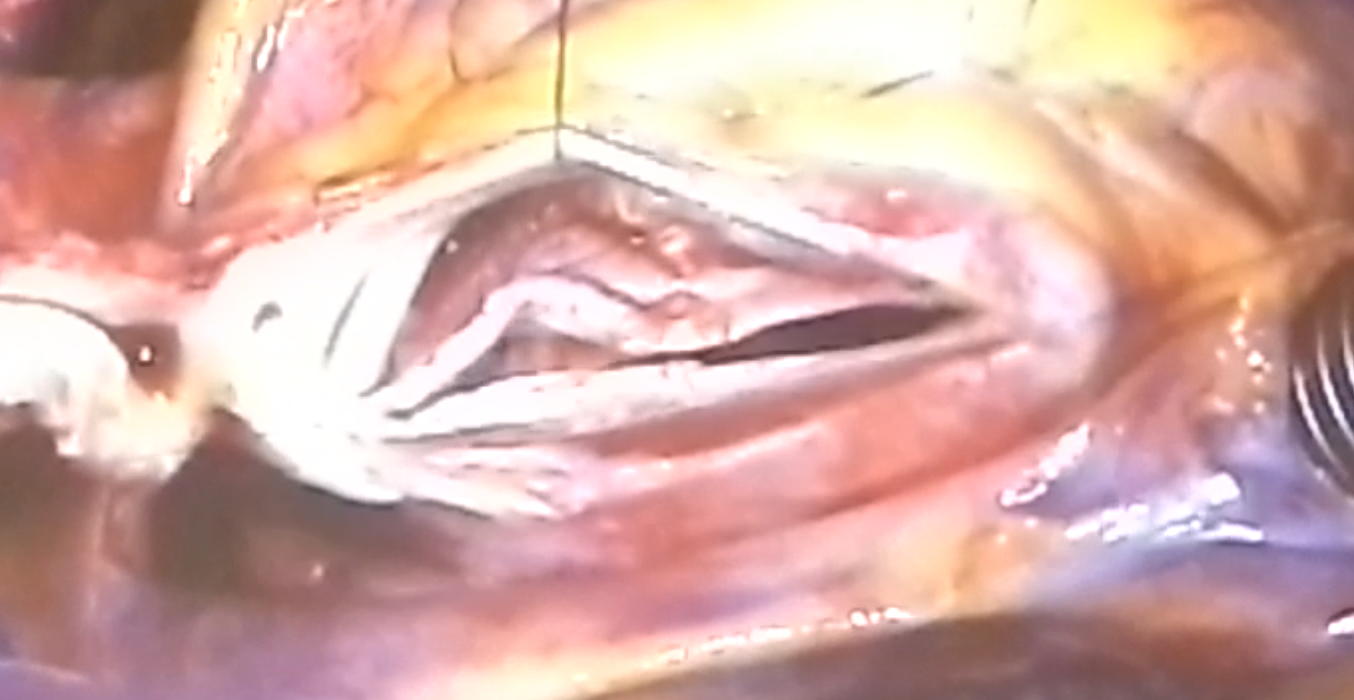

The leaflets of the aortic valve open and close with each heartbeat (systole and diastole). The reason the leaflets close is to prevent blood from backing-up into the heart after it has been pumped out by the contraction of the left ventricle.

The aortic valve leaflets are thin, delicate membranes - similar to wings of a butterfly - that are incredibly strong and durable despite having the appearance of moist parchment paper.

The leaflets are anchored into a razor-thin structure called the aortic annulus - similar to a gasket or O-ring.

Here is where most students go astray in their understanding of the aortic valve. Most people think of the aortic annulus as a planar structure which is horizontal in one plane.

Instead of being a 2-dimensional structure, scientists and clinicians have found that it is surprisingly a 3-dimensional structure.

The attachment site of the valve leaflets extends up into the aortic root.

Hence, with each heartbeat and contraction of the heart, the leaflets move in synchrony with the expansion and contraction of the aortic root, which is a dynamic and compliant structure.

Most people are born the 3 aortic valve leaflets - called tri-leaflet aortic valve.

Here is where it gets interesting.

Approximately 10% of the population are born with 2 aortic valve leaflets, called bicuspid aortic valve (BAV).

People born with BAV don’t have any symptoms or activity limitations and are essentially unaware that they have this condition. We don’t routinely check the aortic valve on all babies that are born to check for BAV, unless there are other heart conditions that are being evaluated.

People with BAV grow normally, lead normal, active healthy lives and are essentially oblivious that their aortic valve is abnormal.

Sometimes, a family doctor may hear a small heart murmur while listening to the heart, but since it is such a minor heart murmur and there are no symptoms or limitations, no workup or evaluation is necessary.

However, there are two concerns that are silently developing during the teenage and early twenties of patients with BAV.

The leaflets of bicuspid aortic valves are susceptible to early degeneration.

The reason for this appears related to the excessive stress and strain on the leaflet tissue to compensate for the asymmetry caused by 2 leaflets opening and closing instead of 3 leaflets.

The second concern that is brewing in people with BAV, is the ascending aorta and aortic root are prone to dilate and expand prematurely.

The associated condition, called aortopathy, stems from a genetic abnormality of the elastic tissue of the ascending aorta which occurs in patients born with BAV.

When you have both a bicuspid aortic valve and an ascending aortic aneurysm, we call it BAV Syndrome. The syndrome part is only when the ascending aorta is affected.

Not everyone with BAV develops BAV Syndrome.

At the genetic level, the gene that regulates how many leaflets develops in the aortic valve is associated with the genes that determine the quality of the elastic tissue of the ascending aorta.

Scientists are still researching this fascinating subject and we don’t yet have a simple blood test to screen for this disease.

Nevertheless, patients with BAV Syndrome are predisposed from birth to have their bicuspid aortic valve where out prematurely and develop an ascending aortic aneurysm.

There is no pill, pharmaceutical or treatment yet discovered which can alter these course of events.

The BAV leaflets get stiff and rigid from the excessive strain and patients usually require open heart surgery somewhere between the ages of 25 and 55.

The decision on when to operate is a complex one.

Of course, if there are symptoms like chest pain and shortness of breath, the decision to undergo surgery is a straightforward one.

Most patients, however, are asymptomatic or don’t have any symptoms.

The BAV is usually detected as an incidental finding as a result of other unrelated heart tests.

The criteria of which patients to offer open heart surgery to are evolving and subject to debate.

Here is where it gets interesting.

Standard criteria to operate on the ascending aorta are based on a size of 5cm in maximal width dimension.

However, since the aortic tissue in the ascending aorta is genetically abnormal and more fragile and prone to tearing, ripping or giving way, the cutoff for patients with BAV Syndrome is 4.5cm.

Many surgeons don’t follow these most recent guideline criteria.

Another matter that is of debate amongst specialists are how much of the aorta to resect and cutout.

Scientific studies have shown that the elastic tissue abnormality in BAV Syndrome involves every bit of the aorta from the aortic valve annulus to the innominate artery which is the first great vessel in the aortic arch.

To adequately eliminate all abnormal tissue and prevent future risk of additional aneurysm development, all tissue should be removed using a procedure called a hemi-arch wth circulatory arrest.

This is an extension of open heart surgery which enables heart surgeons to trim all of the aortic tissue to the level of the innominate artery.

Without getting too technical, when we do open heart surgery, we have to place a metal cross clamp across the ascending aorta in order to stop the heart and allow us to replace the aortic valve and aortic root.

However, by placing the cross clamp on the aorta, we are able to resect the part of the aorta where the clamp is located and thus, by definition, we leave behind some diseased tissue.

Not all surgeons routinely perform a hemi-arch procedure for patients with BAV Syndrome, and thus these patients are at small risk of developing an aortic aneurysm in the small rim of tissue left behind where the cross clamp was located.

I prefer to resect this part of the aorta because scientific studies have shown that this aortic tissue is abnormal.

In a hemi-arch procedure, we temporarily remove the cross clamp in the ascending aorta and stop all blood flow to the body and brain. We quickly sew a synthetic, cloth graft to the transacted aorta and then place a clamp back on the new surgical graft and restart the blood flow to the brain and body.

There are some additional risks associated with this aspect of the procedure, but in centers where this is done routinely, it can be performed with minimal risk to the patient.

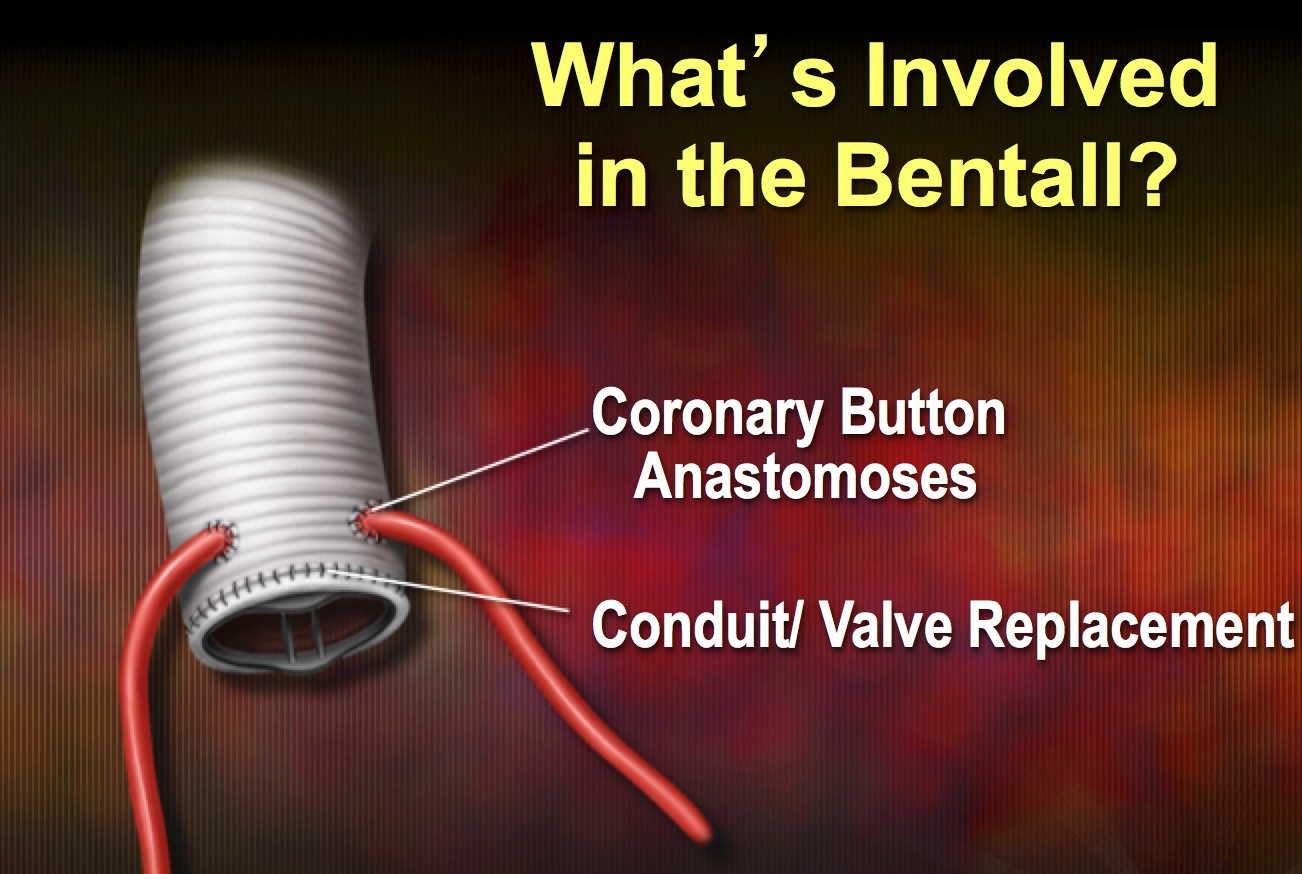

In addition, to a hemi-arch, we usually perform a valve-sparing root replacement where we can save a functionally normal bicuspid aortic valve. If the BAV is not functioning properly, then we can replace it as part of a Bentall Procedure,

As you can appreciate, BAV is a very complex subject and we still have a lot to learn.

At the end of the day, as with all surgical decisions, from a risk-reward standpoint, for patients to benefit, the risk of surgery must be lower than the risk of complications from their inherent disease.

Patients with BAV and BAV Syndrome have many things to consider when evaluating their options, such as how to handle the aortic valve, among other things. In my experience, it can be overwhelming for patients and their families and can lead to a lot of stress when dealing with this problem. That is why I always spend a lot of time carefully explaining all the options with patients, because the better informed these patients are, the more confident they can be in making their best decision.

Back to the title of this piece: Double Trouble - refers to the fact that patients with BAV most frequently have two issues, an abnormal heart valve from birth and associated abnormal ascending aortic tissue. Hence, Double Trouble.

Feel free to pass this along to other people or family members who might benefit from this information.

For more information on Bicuspid Aortic Valve Surgery along with Open Heart Surgery, feel free to check out my other website.

Was this post informative?

Subscribe to my newsletter to learn more about the aorta, its diseases, and how to treat them.

Comments

Share your thoughts below — I try to get back to as many comments as possible.